The Shocking Past of Europe’s Time of Consuming Mummies

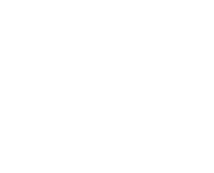

The Victorian era was a time of strange traditions and practices. One such custom involved a long-standing fascination with Egypt, particularly the mummies. This Victorian fascination with Egyptian culture gave way to a gravely bizarre practice.

The elite in Victorian society consumed mummies! Let’s unpack how this behavior came to be and what benefits Victorians thought they were achieving by participating in this strange practice.

Misunderstanding of an Ancient Word Leads to the Mummy Craze

The word “mumia” in Arabic refers to a natural asphalt Egyptians used to keep dead bodies from rotting. Europeans thought this substance made dead bodies last longer and could make people healthy. Thus, they brought it to use as medicine and as a coloring.

Source: Pinterest

Some devious businesspeople sold dead bodies to be used as mumia. People in the Victoria era thought it could make many sicknesses go away and ate it in different ways, such as small balls, dust, liquid, and sweet brown food.

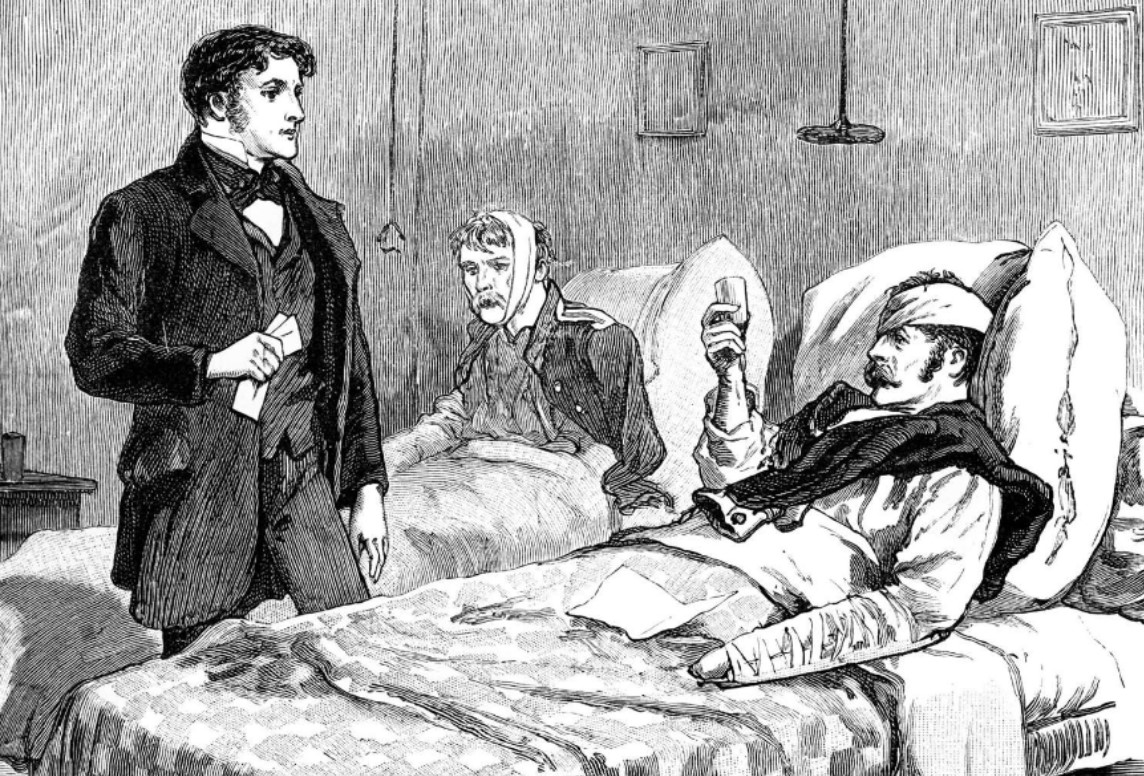

How King Charles II of England Became a Mummy Addict

King Charles II (1630–1685) was fascinated by alchemy and medicine. He used the mummy dust as an anti-aging and healing remedy and drank a tincture of human skulls, named “The King’s Drops.”

Source: msn.com

He shared a common belief with many other royals and nobles: mummies were a cosmetic and a tonic with magical properties. They ate mummies to gain power and to ward off evil, bad luck, and death.

Trying to Grow Wheat from Mummy Seeds

Some Victorians used mummies to grow wheat from seeds found in tombs. They believed this wheat was superior to others and magical for health and fertility. They also felt closer to ancient Egyptians through this practice.

Source: msn.com

Wheat from mummy seeds was a fallacy—the end product was terrible, and sometimes toxic. The Victorians had been fooled or at least misguided. Unfortunately, they squandered their resources on a worthless and risky experiment.

How Our Attitude Towards Mummies Has Changed

The Victorian era’s interest in mummification, caused by confusion and mystery, led to some strange things. From eating corpses for their imagined health benefits to trying to grow food from old seeds, these practices demonstrate a time when people thought they knew more than they did.

Source: msn.com

Today, we approach mummies with a sense of respect and reverence, acknowledging their invaluable contribution to our understanding of ancient Egyptian culture. This journey from consumption to conservation is a powerful reminder of how our attitudes toward history and cultural heritage can evolve.