Ship found in Arctic 168 Years After Doomed Northwest Passage Attempt

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror: An Arctic Mystery That Baffled the Entire World

Sir John Franklin’s final expedition’s fate was previously unknown until the wreckage of the HMS Erebus and Terror were found in 2014 and 2016, respectively. It’s still a big mystery in the world of marine research. For some reason, his 1845 expedition on the ships Erebus and Terror to navigate the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific failed.

All 129 men on the expedition perished, and for the last 150 years, the story of their mission has captivated people across the world. Will we, however, ever learn the whole truth?

How It All Began

Topsham, Devon, was the site of the construction and launch of HMS Terror in June 1813. This ship’s hull was designed to resist the force of explosions, as it was a bomb vessel. Terror‘s first role in history was as a warship, fighting against the United States in various engagements during the War of 1812.

commons.wikimedia.org

In 1826, the Royal Navy constructed HMS Erebus at Pembroke Dockyard in Wales. Once its time as a bomb ship was up, Terror was repurposed into an exploration spacecraft. It traveled to the Arctic, where it was severely damaged by ice in a region called Frozen Strait.

More Trips Planned for the Ships

The HMS Erebus and HMS Terror left Britain for what is now Nunavut in Northern Canada in May 1845. It was believed that the North-West Passage, the seaway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, was now within reach after extensive explorations of the Arctic coastline.

en.wikipedia.org

It was an exciting time for everyone given not a lot of people are able to explore various places, let alone ships like HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. Who would have thought that it would be the beginning of a journey that would create a massive impact on history?

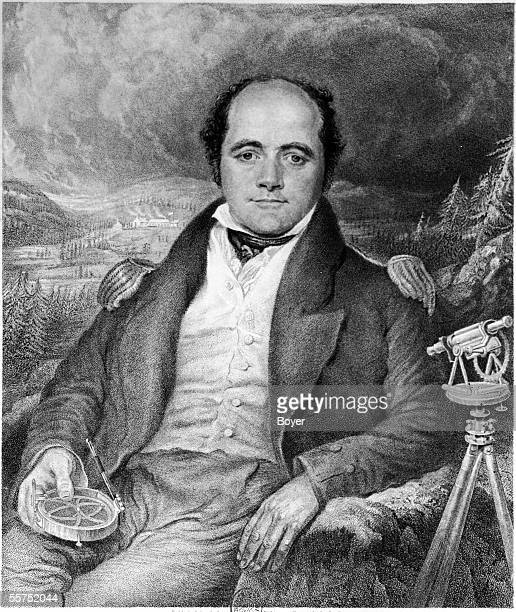

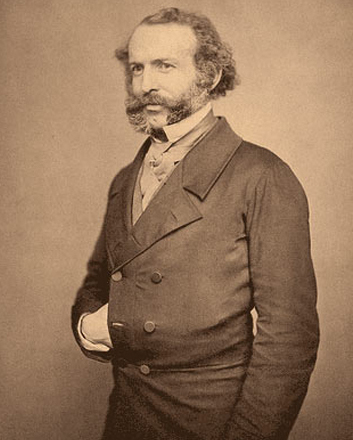

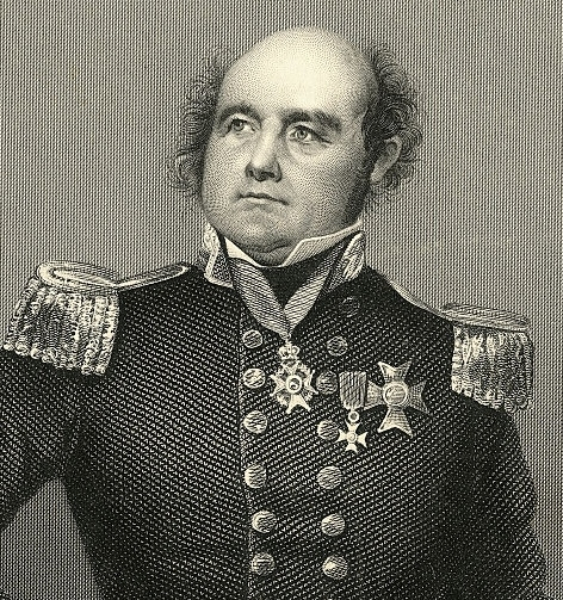

The Leader of the Pack

Sir John Franklin (born in 1786), a Royal Navy commander with an impressive resume, including participation in the legendary Battle of Trafalgar and nearly six years as lieutenant governor of modern-day Tasmania, led the mission.

commons.wikimedia.org

Believe it or not, Franklin wasn’t the first choice to captain such an important expedition. For varying reasons, the other men approached had declined the offer to lead a crew to the arctic region. Whatever the case, it would appear that Franklin was the man for the job—and so he was indeed.

A Captain Who Never Wavered

Franklin led around 130 soldiers into the Arctic in spite the fact that he was 59 years old at the time of the mission. He was a seasoned sailor who knew the ins and outs of the sea—something not a lot of men can brag about.

Photo by Boyer/Roger Viollet via Getty Images

The man had one main goal, and that was to reach the Pacific Ocean from far above Canada, which would require navigating over several unexplored islands and a great deal of ice. It sounded like an impossible dream, but Franklin was determined to make it happen.

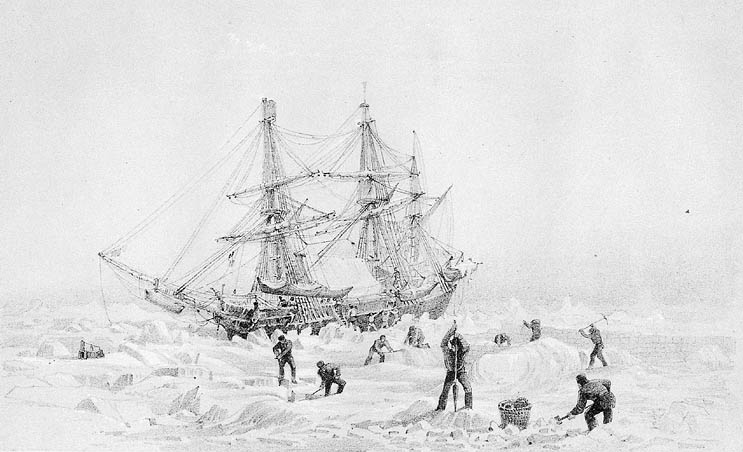

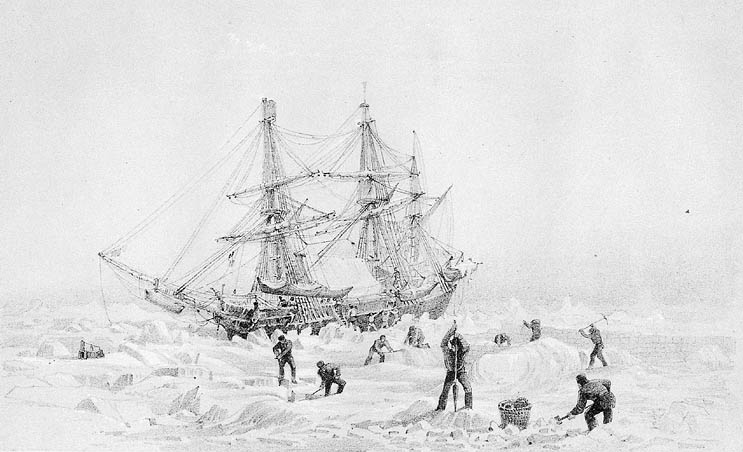

Magnificent Masters of the Sea

The British Empire spent the whole of the 19th century embarking on a series of disastrous wars. Still, the expedition’s captains were confident in their vessels’ ability to meet the challenge. There was widespread agreement that both the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus were technological marvels for their day.

Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

First of all, the fact that the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror used to be warships is enough proof that they are more than capable of long journeys. They’ve been through a lot and have weathered many storms. As long as there’s a crew on board, then they’re good to go!

Equipped with the Best Features

Each vessel also featured a steam-powered propeller that could reach speeds of around four knots, and their bows were strengthened with iron to withstand the impact of the ice pack. That steam also heated the inside. It had everything every navigator could possibly need or want.

National Maritime Museum

The fleet set sail from England in May, first bound for Greenland and then Canada; by the end of July, they had arrived in Lancaster Sound at the start of the Northwest Passage. After that point, reliable historical records start to disappear.

Making Their Away Around the Channel

Franklin chose to spend the winter months off Beechey Island, a barren rock and ice outcrop located between Lancaster Sound and Wellington Channel. Two navy warships under Franklin’s command headed north through the Wellington Channel before making a southerly swing toward Beechey Island, where they intended to spend the season.

ceb.wikipedia.org

They set off in the spring, sailing south along Peel Sound, but were unable to make it past the northern tip of King William Island due to the ice flow in McClintock Channel.

A Beautiful and Dangerous Place

Expedition teams were occasionally at the mercy of the enormous pressure of the sea ice and the unexpected behavior of icebergs in the Arctic, an area known for its frigid fog and churning waters. Occasionally, the scenery was also stunningly gorgeous, with vivid hues and starry sky.

Anyone who’d see the scenery firsthand would usually be in awe of its extraordinary beauty. That’s also likely one of the many reasons why explorers are keen to know more about it. There could be many secrets surrounding the Arctic, and Franklin’s men couldn’t wait to know what it was.

The Back of Beyond

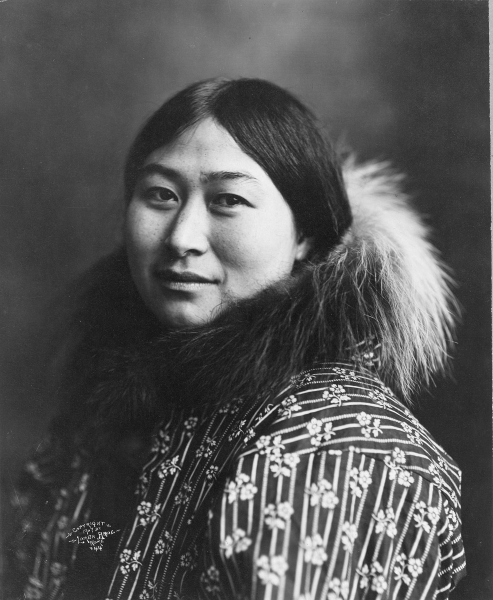

Inuit seldom ventured to this lonely region known as Tununiq, meaning ‘the back of beyond,’ where Franklin’s ship became icebound. Like previous missions, this one found that it was impossible to rely on locals for food, clothes, or oil. However, they had adequate food and water for three years, and British expeditions were accustomed to surviving Arctic winters.

en.wikipedia.org

It shouldn’t be too difficult to manage this situation, mainly since Franklin was used to similar problems. Little did they know that they would be in a dire predicament in just a matter of days.

Some Discoveries Made in the Region

Upon arrival, the group discovered that three crew members were buried on the island, and their remains, which had been admirably preserved by the island’s severe conditions, would one day provide a crucial clue as to the expedition’s fate.

en.wikipedia.org

Apparently, Terror and Erebus spent the winter of 1846 in Beechey. By the time the summer arrived, the ships had made it as far south as King William Island, but the ice had already begun to advance again. From there, their problems would only get much worse.

The First Red Flag

Information that wasn’t transmitted through telegraph or semaphore lines was limited to the speed of trains and ships during this time period. It wasn’t out of the ordinary to go years without hearing back from the other side of the globe.

pt.wikipedia.org

It took nearly three years after the ships set sail before there was widespread concern about the expedition’s fate. What could have happened that the sailors were unable to let anyone know of their whereabouts? Worse, would they ever have the opportunity to do so unless danger was at hand?

It Was Time for a Search and Rescue

After hearing nothing from Franklin and his crew in 1848, the British Admiralty decided to mount a rescue mission by land and water. If there was no word from the Terror or Erebus, then it’s safe to assume the worst must have happened. The group was likely in trouble.

pt.wikipedia.org

The only problem was that it would take some time before anyone could reach their whereabouts. No one also knew their actual location. When a small group of rescuers finally made it to Beechey Island in 1850, they discovered the burial grounds dated 1846.

Almost Impossible to Find

Later, in 1854, explorer John Rae met several Inuit in Pelly Bay who informed him that as many as forty Englishmen had died of famine and sickness near the mouth of the Back River, which lies roughly straight south of King William Island.

ru.wikipedia.org

Could this be a clue as to where Franklin and his men were? It was unclear whether or not they had survived or marooned in another area. Perhaps, these were the men the Inuit talked about in John Rae’s accounts. They’ll find out soon enough.

Unsure About the Situation

At first, John Rae was unsure whether or not these locals knew what they were talking about, let alone understand what he was trying to say. To address this apprehension, the Inuit brought out a variety of objects, including a telescope, to prove their story to Rae.

da.wikipedia.org

And it gets worse: they said the Englishmen had eaten each other before they died. The stories they shared were unimaginable—these couldn’t be the same men. What could have happened that they’d resort to such barbaric actions?

Just Trying to Survive

No one in their right mind would believe what the Inuit said, but Rae knew he had no other evidence. He had to take their word for it. As such, Rae was duty-bound to share the news. He faithfully reported the grisly facts to the British Admiralty whether he liked it or not.

de.wikipedia.org

In a transmission, Rae wrote that judging by the state of the crewmembers’ bodies, they had to do what they needed in order to live—eat each other. Cannibalism is a horrible way to go, so it’s regrettable that they even considered it as an option.

The News Shocked the Nation

The population in Britain understandably panicked after hearing this news from the Admiralty. Everyone freaked out over the information, mainly since cannibalism was mentioned. Famous author Charles Dickens even wrote about it in his magazine, but he merely wrote it off as chatter.

Goaway Travel

The author even went so far as to imply that the locals were responsible for the deaths of the sailors. Again, no one could disprove his claims, but it did send a wave of concern throughout the area. At this rate, no one would want to set sail ever again.

More Evidence Has Arrived

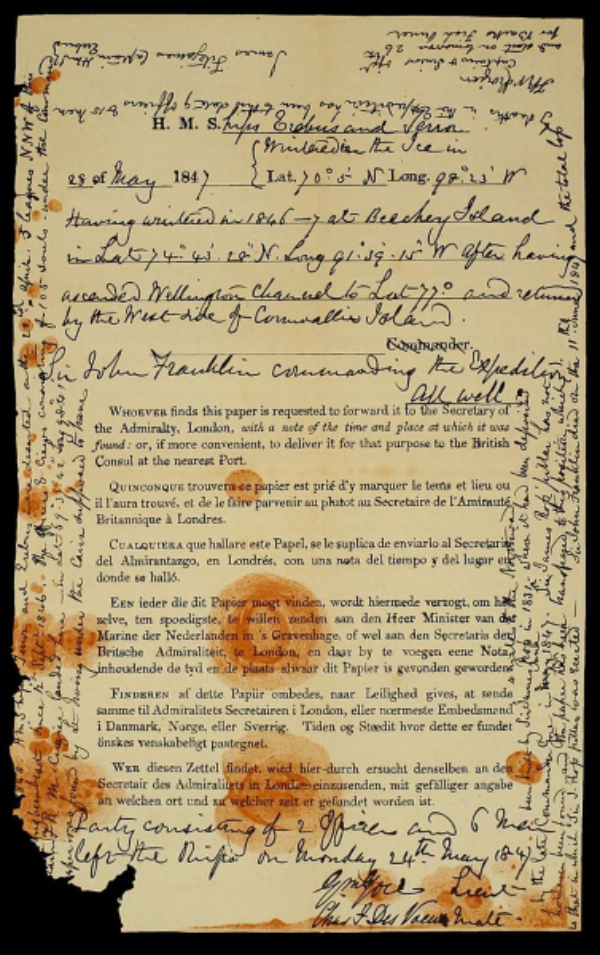

Yet, in 1859, further clues pointed to the fact that something had gone terribly wrong with Franklin’s voyage. A tin canister with a letter with two messages written by separate people was discovered inside a rock cairn in King William Island’s far north.

steenman Garvera

After spending the winter of 1846-1847 in camp, the expedition sent the first communication in May 1847 along predetermined lines, in which they reported that all was well. They also shared the ship’s coordinates and the usual crew headcount. It would appear like a typical note, and nothing was wrong.

The Second Message was Clearer

The following letter provided a considerably bleaker report. Only one document, the Victory Point Note, dating back to 1859, provided any clues concerning what took place. Notes put in the margins of this generic Admiralty form indicated that the ships had been abandoned on April 22, 1848, after being trapped in the ice since September 12, 1846.

nl.wikipedia.org

Over a hundred and five officers and crew members, headed by Captain F. R. M. Crozier, had set out on foot for the Back River. More importantly, the message stated unequivocally that John Franklin had passed away on June 11, 1847.

An Experience to Remember

Typically, we would brace for winter by wearing warm clothes and ensuring the heating at home is at its optimal function. Yet, imagine what it would be like when one is in the Arctic. Even pulling off a balaclava in subzero temperatures might shred the skin and beard from the chin, so the men on Franklin’s ships had their work cut out for them.

en.wikipedia.org

Consequently, the crews made all necessary preparations. The good news is that they knew what they were in for the minute they signed up for the journey. But things can still go out of hand.

People Tried to Look for Them Again

After two years had passed since anybody had heard from the Franklin expedition, the first of several missions set out to find them, or at least find out what had become of Erebus and Terror. The tragic death of British hero Sir John Franklin made headlines throughout the country, and the citizens hoped to unveil the truth about his demise.

commons.m.wikimedia.org

A total of almost 30 expeditions set out for the Arctic between 1847 and 1880, all with the same goal of discovering what happened to the mission. As far as everyone knows, the effort was made in all possible areas.

Franklin’s Wife Wanted Answers

In 1850, the Admiralty sent both land and marine missions under pressure from Lady Jane Franklin, Parliament, and the British press. Between 1850 and 1857, Lady Franklin provided financial assistance for the fitting out of five search ships, with Leopold McClintock’s trip on the yacht Fox giving the first recorded proof of the men’s fate.

en.wikipedia.org

After the expedition’s terrible conclusion became public knowledge, Lady Franklin probably had a role in changing the story such that her husband was celebrated as the supposed discoverer of the Northwest Passage.

Relics Were Popping Up

For the following 30 years, reports and souvenirs like tin cans, ski goggles, and silverware trickled back to Britain. All of these artifacts together told the story of the ship’s crew’s demise from scurvy and hunger. Meanwhile, there were complications with some of the rescue efforts.

pikabu.ru

At a glance, one might say that some form of higher power didn’t want anyone to know about Franklin and his team. Fate had other plans, and problems kept on arising no matter what the rescuers did.

Rescuers Did Their Best

Another ship called the HMS Resolute decided to give it another try, but the rescue never came to fruition. After the crew of the HMS Resolute gave up and abandoned the ship while stuck in the ice in 1854, it wasn’t found until the following year by an American whaler.

en.wikipedia.org

Interestingly, the whalers made the most out of the ship’s remains by removing some parts and immortalizing them by making some furniture. For instance, the Resolute desk, fashioned from salvaged ship wood, is now permanently installed in the Oval Office.

Finding the Mysterious Boats

The vessels’ whereabouts remained a mystery, and people thought that was the end of it. It wasn’t until 2014 that the HMS Erebus was found sunken in the Queen Maud Gulf, a considerable distance from King William Island.

en.wikipedia.org

Two years later, the HMS Terror was finally discovered in a rather excellent shape just to the south of the island. It’s been more than a century since the boats disappeared, yet here they were, as if waiting for the right moment to finally emerge from the ocean.

Stories Are Not Enough

Of course, the Inuit have supplied some firsthand reports of the ships disappearing, but it is impossible to establish the times and places that are mentioned in those recalls. It was a matter of having faith in the stories that were shared—they basically took what they could get.

ar.wikipedia.org

It is difficult to determine why the ships sank or what caused the crew to leave them. If only one of them at least survived to tell the tale, then people won’t have to speculate anything.

An Autopsy of the Past

The most important question was, what had become of the sailors? When Franklin passed, did they also assume that would be the conclusion of their journey? Perhaps the men also hoped to pursue the trip, but the Arctic got the best of them.

en.wikipedia.org

It turns out that tuberculosis and pneumonia contributed to the deaths of the Beechey Island crew. Research has shown that it may have been made worse by lead poisoning, and these claims became even more apparent when an autopsy was performed in the 1980s.

It Led to Lead Poisoning

It’s possible that the ship’s water delivery pipelines, or inadequately sealed cans, contributed to the increased lead levels. While greater lead levels were normal in men and women at the time, the pipes may have been the principal problem in this case because other British crews across the world ate from cans cooked in a similar fashion without incurring severe lead poisoning.

Youtube

Nevertheless, it was good to have some small clues regarding the downfall of HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, no matter how small. It was critical to put together this significant part of history, and now was the time for it.

They Were Ill Toward the End

The crew had been weakened by disease and malnutrition during their two winters on the ice, and they finally decided that heading south was their best chance at survival. However, making their way through the wilderness presented their own challenges, and they were unable to avoid a landing approach into the unspeakable horror due to a lack of appropriate equipment.

en.m.wikipedia.org

The researchers found even more chilling items. Bone fragments associated with the voyage discovered on King William Island in the early 1990s showed signs of butchery. It was like a horror story straight from the movies.

The Case Has Finally Been Solved

With the discovery of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror in 2014 and 2016, respectively, the fate of Franklin’s last mission was no longer a mystery. While working with the Inuit Heritage Trust, Parks Canada’s underwater archaeologists have made more dives, uncovering more intriguing artifacts.

Meanwhile, the world can’t help but be enamored by Franklin’s story, so much so that it even became an idea for a television series in 2022. Although Franklin’s expedition initially set out to ‘conquer’ the Arctic, the region ultimately proved too formidable in the end.