Cave of Horrors Reveals New Dead Sea Scrolls and a 6,000-Year-Old Skeleton

What you are about to read has the makings of a mystery novel, but it’s all true. In 1946, the Qumran or Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered by accident. Historians call the scrolls the most valuable artifacts uncovered in the Holy Land and their discovery an epic archaeological tale.

Yet, the story is far from over, as the Qumran region continues to reveal more ancient secrets.

The Incredible Finding of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea scrolls are ancient Jewish texts written before 100 CE (Common Era), thought to be one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. Many believe the Essenes, a Judaism sect from the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE (Before Common Era), wrote the scrolls in Hebrew, Greek, and regional dialects of Aramaic.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Bedouin shepherds discovered the parchment scrolls hidden in a cave in 1946. Over the course of the next century, scholars would pour over the texts to learn about events that took place more than two millennia ago.

Accidentally Discovered by the Most Unlikely Person

In a long-forgotten cave, a young shepherd from Ta’amireh found Hebrew manuscripts preserved in jars after his harmless search for a lost goat.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Three Bedouin shepherds were tending to their goats and sheep near Qumran, an ancient city in what is now the West Bank. When one of the young shepherds threw a rock into a crack in a cliff, he was startled to hear something break. Another of the shepherds later fell into the cave and discovered a number of enormous clay jars.

Deliberating What to Do With Them

The three lucky Bedouin shepherds were Muhammed edh-Dhib, his cousin Jum’a Muhammed, and Khalil Musa. Though Muhammed was the first to spot the jars, Edh-Dhib was the one who fell into the cave. It was then that he saw the seven clay jars with the papyrus and leather scrolls.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Edh-Dhib took a few scrolls—later identified as the Isaiah Scroll, the Habakkuk Commentary, and the Community Rule—back to the camp to show his family. Luckily, all of the documents remained undamaged. While they deliberated what to do with them, the Bedouin shepherds kept the ancient manuscripts hanging on a tent pole and showed them off to their people.

The Bedouins Decide to Sell the Scrolls

Unaware of their significance, the Bedouins tried to sell the scrolls. First, they consulted a trader in Bethlehem named Ibrahim’ Ijha. Ijha believed that the manuscripts were stolen from a synagogue, and returned them, claiming they had little value.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

However, the Bedouins persevered, travelling next to a local market, where a Christian Syrian offered to buy the scrolls. A sheik overheard them and recommended they visit Kando, a part-time antique dealer who could buy their discovery at a fair price. Thus, the Bedouins went home with money and minus three scrolls. The ancient documents would eventually find their way into the hands of several academics who determined their age to be well over 2,000 years.

Searching the Qumran Caves

Archaelogists soon found caves containing eleven scrolls and even a human settlement as one discovery led to another. No stone has been left unturned at the Qumran site since 1946 and there have been extensive excavations in the human settlement in the area.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

In 1947, John C. Trever of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) examined the original seven scrolls. He discovered parallels between its texts and those found in the Nash Papyrus, the earliest biblical document at the time. Later, some of the scrolls were transported to Beirut, Lebanon, for safekeeping due to the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Searching for Ground Zero

Metropolitan archbishop Mar Samuel delivered more scroll pieces to Professor Ovid R. Sellers, the new ASOR director, in September 1948. Although it was nearly two years after the scrolls were found, researchers still couldn’t access the original cave due to the Arab-Israeli War.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Sellers attempted to pay Syrian locals to find the cave, but he was unable to meet their price. The Jordanian government eventually allowed the Arab Legion to examine the old Qumran cave in early 1949. The legion confirmed it was indeed where the original scroll fragments came from, so they named it Cave 1.

Excavating Some More Caves

The Jordanian Department of Antiquities, under the direction of Gerald Lankester Harding and Roland de Vaux, conducted the initial excavation of the site. After a month, in 1949, the site was named Cave 1 at Qumran.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The department then explored another cave one kilometer north of Wadi Qumran, where it found 70 new fragments, including pieces of the first seven scrolls. The new fragments, along with jars and linen cloths, confirmed the dates of the scrolls predicted by paleographic research.

The Search for More Scrolls

The Bedouins kept looking for more scrolls as the first ones proved to be a lucrative source of cash. Cave 1 was emptied of artifacts after archaeological excavation but as the Bedouins found more materials, it was clear to scholars that Cave 1 was not the only place they had to dig.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Roland de Vaux and the ASOR crew then started full excavations in Qumran. In February of 1952, the Bedouins found thirty pieces in the area that would later be called Cave 2. Here, archaeologists unearthed 300 manuscript pieces from 33 different texts, including fragments of the Hebrew books, ‘Jubilees,’ and the ‘Wisdom of Sirach.’

How the World Found Out

Unlike other archaeological discoveries, the Dead Sea scrolls did not have a big unveiling, despite their historical importance. The world found out about them through an advertisement in the Wall Street Journal that mentioned “The Four Dead Sea Scrolls.”

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Archbishop Mar Samuel made the announcement, after he smuggled the manuscripts to a Syrian church in New Jersey in the late 1940s due to unrest in Palestine. The scrolls stayed in the church until he made the decision to sell them. Yigael Yadin, an Israeli archaeologist, negotiated with an American broker to purchase the four scrolls for the State of Israel.

The Great Isaiah Scroll

One of the first seven Dead Sea scrolls was the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa). Except for a few minor damaged passages, the Hebrew scroll contains the whole Book of Isaiah from start to finish.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

It is the oldest complete copy of the Book of Isaiah, a thousand years older than other known Hebrew manuscripts at the time. The manuscript is large, measuring 734 cm, and is inscribed on 17 sheets of parchment. What’s more is that it is the only fragment from Cave 1 that is completely preserved.

Habakkuk Commentary or Pesher

Another of the original seven Dead Sea scrolls, the Habakkuk Commentary or Pesher Habakkuk, came into public light in 1952. The remarkably well-preserved document is currently known as 1QpHab and is widely studied, having been discovered and published early.

.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The Pesher links several modern people to the scroll with their titles. It mentions the Teacher of Righteousness, a figure found in some other Dead Sea scrolls who is an ideal and charismatic leader of the Jewish community. The identity of this figure is still under speculation with many theories coming up.

The Genesis Apocryphon is in Aramaic

Another discovery at Cave 1 was The Genesis Apocryphon, also called Tales of the Patriarchs or the Apocalypse of Lamech. Classified as 1QapGen, it is has four leather sheets with Aramaic text, and it is the most damaged of the original seven scrolls.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The text captures a conversation between father and son, Lamech and Noah. Scholars think the Essenes may have written the Genesis Apocryphon. Roland de Vaux claims it might be an original document as there aren’t any copies in the other 820 fragments at Qumran.

Researchers Already Knew About This Scroll

1952 saw the discovery of the Damascus Document in Cave 4. What’s interesting is that researchers already knew this existed. An 1897 excavation recovered two parts of the Damascus document from an Egyptian synagogue and archived them in the Cairo Geniza collection. The Document is regarded as one of the primary Jewish texts in Qumran.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The Damascus Document is, however, a fragmented manuscript and scholars have attempted to piece together the original text. Still, the proper order of the text remains a mystery and the medieval version seems shorter than the Qumran version of the document.

The Dead Sea Scrolls' Origins

Scholars continue to disagree about the origins of the Dead Sea Scrolls but they were likely composed between 150 BCE and 70 CE Historians claim that a Jewish Essenes population in Qumran created the texts before Roman armies destroyed their town in 70 CE. The austere and communal Essenes were one of the four Jewish sects in Judea before and during the Roman era.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Those who support this theory compare the writings of the Roman, Flavius Josephus, and the Community Rule, a scroll describing Jewish ordinances, with both texts describing similar ceremonies and rituals.

Written in Several Languages

Most of the scrolls are in Hebrew, although a few are in the obsolete paleo-Hebrew script of the fifth century BCE. Others are in Aramaic, the primary language of many Jews between the sixth century BCE and the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE; it was even the language of Jesus.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Additionally, numerous manuscripts include Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible, a language also used by the Essenes. Although there is no way to detect the language of a severely fragmented document, some Qumran texts, like the Enoch and Tobit, are both preserved in Hebrew and Aramaic.

One of the Scrolls is a Treasure Map

The Copper Scroll, a sort of ancient treasure map that identifies dozens of gold and silver caches, is one of the most intriguing texts from Qumran. Discovered in Cave 3, close to Khirbet Qumran, it is very different from the others, mainly because it is not a literary work.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

This strange document has peculiar codes in Hebrew and Greek letters chipped onto metal sheets. Some speculate this was done as a preservation technique, even though the other documents are in ink on parchment or leather. The metal scrolls outline 64 underground vaults around Israel that are said to have treasures hidden for safekeeping, however, these treasure hoards have never been found.

The Shrine of the Book

Jerusalem’s Givat Ram area is home to the Israel Museum’s Shrine of the Book, where priceless artifacts like the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Aleppo Codex are kept. The shrine is constructed as a white dome that covers an area two-thirds below ground level, where a pool reflects the shrine on all sides.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

A black basalt wall is located opposite the white dome, symbolizing the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness, according to some interpretations. Scholars say that the colors and shapes of the building are based on the imagery of the Scroll of the War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness.

Home of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The shrine was built in 1965 with donations from the family of the Hungarian-Jewish philanthropist, David Samuel Gottesman. Over the course of seven years, architects Armand Phillip Bartos, Frederick John Kiesler, and Gezer Heller constructed the building.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The Great Isaiah Scroll is the centerpiece of the Shrine of the Book. All seven original scrolls are on display in the shrine, on a rotating basis as the fragile texts cannot be on continuous display. When a scroll has been put on view for three to six months, it is taken out of its showcase and briefly stored in a designated area where it “rests” from public view.

Digital Preservation of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Israel Museum in Jerusalem has the Shrine of the Book. The Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Project of the museum lets online users view and explore these most ancient writings from the Second Temple period in unprecedented detail.

Source: BBC News / Youtube

The newly launched website, a collaboration with Google, gives access to high-resolution, searchable photos of the scrolls and short videos that translate the scrolls and provide background details. So far, the project has digitally preserved the Great Isaiah Scroll, the Community Rule Scroll, the Commentary on Habakkuk Scroll, the Temple Scroll, and the War Scroll.

There’s More to the Story

Many museums have also temporarily displayed smaller fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls since they were discovered. In 1965, the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., had people lining up for an exhibition of the scrolls. Plus, as it turns out, there are more scrolls to see.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

In March 2021, new fragments were discovered in a cave in the Judean Desert, the first ones in 60 years. The discovery happened during a national initiative that was started in 2017 to search all Judean Desert caves and ravines for artifacts from prehistoric and biblical eras.

The Cave of Horrors

The Cave of Horrors is one of eight caverns in the Na’al’ever canyon where Jews hid during an insurrection against Roman rule in 132-135 CE. Simon bar Kochba led the insurrection and many of his followers believed him to be the Messiah.

Source: BBC News / Youtube

Archaeologists have known about the historical cave since 1953, but it wasn’t discovered until 1961. Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni and his team made the discovery as part of an extensive operation by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) to look for new texts.

It's Hidden from View

It’s no surprise that a place as isolated as this cave would be used as a hiding spot. According to Aharoni, the cavern’s entrance is located 80 meters below the rim and has a drop of several hundred meters.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

In 1955, explorers of the cave descended a 100-meter-long rope ladder to search for the cave’s entrance. Numerous skeletons, including those of children, were found inside the cave, earning it the moniker “Cave of Horror.” Personal documents, a Hebrew prayer written in pieces, and the scrolls were some of the belongings found alongside the skeletons.

A New Cave Discovered

The Cave of Horrors was found six years after the Dead Sea Scrolls. The discovery was like something out of an Indiana Jones film. A Roman camp’s ruins at the cliff’s peak indicate that the refugees who took sanctuary in the cave perished during a Roman siege.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The lack of injuries on the skeletons indicates that their demise may have been brought on by starvation, dehydration, or smoke inhalation from a fire in the cave’s central chamber. The refugees buried their most valuable possessions, including a scroll whose fragments were found in 2021. After the cave’s initial discovery, the Israel Antiquities Authority reopened the dig in 2017.

Unearthing More Artifacts

Archaeologists found exceptional items as they dug deeper into the cave complex, consisting of eight caves resting at the base of a steep slope. The oldest woven basket ever discovered, going back 10,000 years, was unearthed inside the cavern in 2021. Although it was obvious that there had been theft inside the cave, the basket was miraculously found unharmed just ten centimeters from the thief’s footprints.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

In addition to the basket, archaeologists also discovered older Dead Sea scrolls and Bar Kokhba Revolt-era coinage. Those are not the only things the diggers found in the Cave of Horrors.

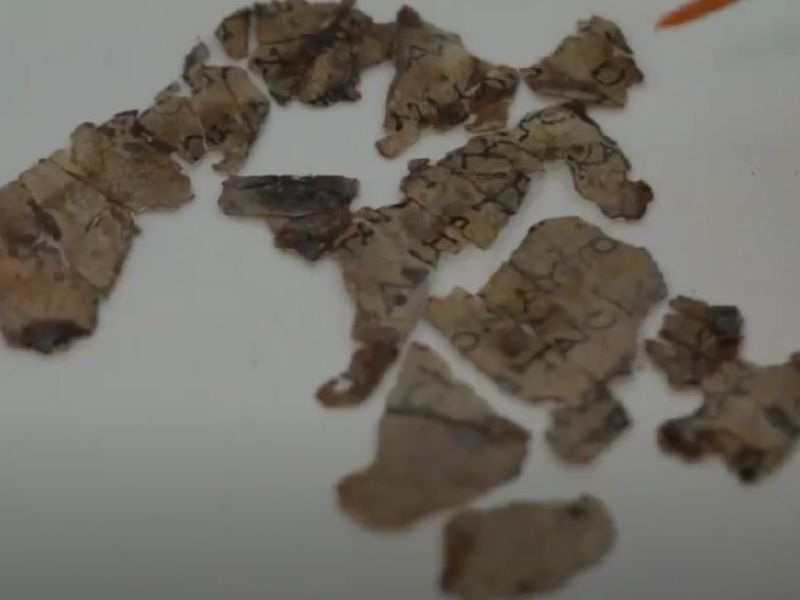

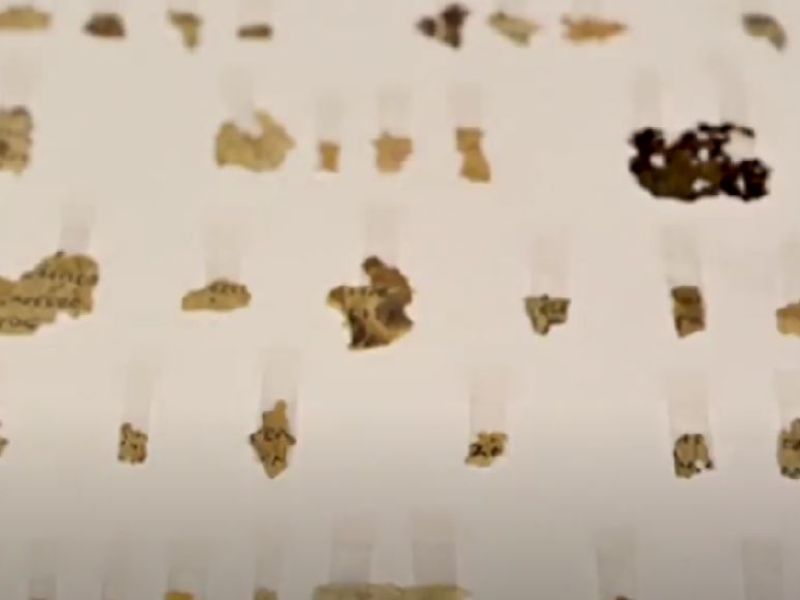

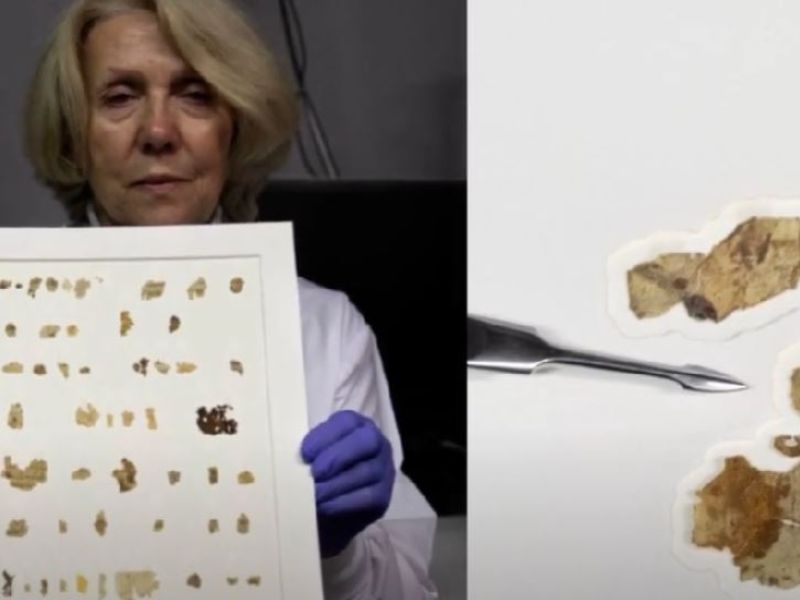

Dead Sea Scrolls Again

Dozens of Dead Sea Scroll fragments were found in 2021, most likely stashed away in the hidden cave between 132 and 136 CE during the unsuccessful Bar Kokhba uprising against the Romans.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Some scroll pieces are Greek translations of the Jewish Tanakh’s Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets, containing Nahum and Zechariah’s biblical books. The sole Hebrew in the text, however, is God’s name, as the scrolls were likely secreted during the revolt.

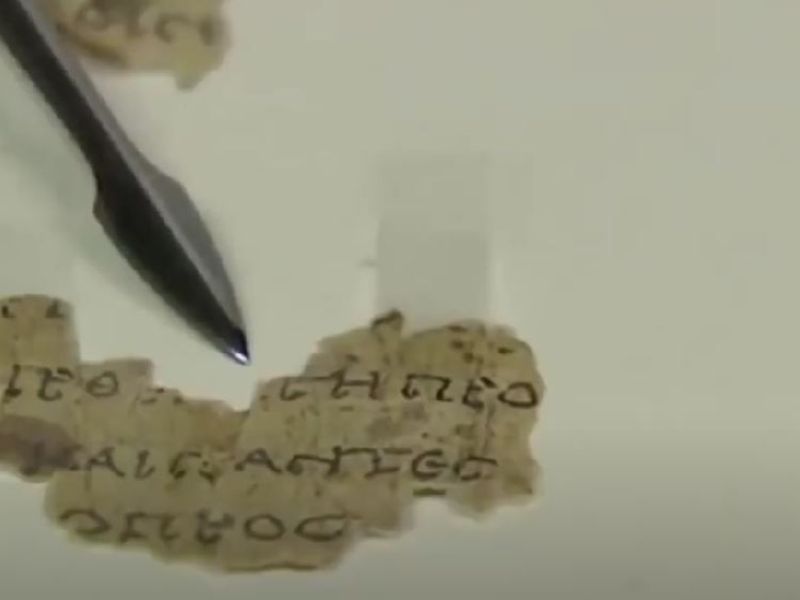

Why was God’s Name in Hebrew?

The Old Testament was translated into Greek for Greek-speaking Jews who were beginning to forget their Hebrew heritage. Documents like the epistles of Aristeas indicate that Greek translations started some 200 years before Christ. This is why the sole Hebrew word in the new scrolls intrigued archaelogists.

Source: BBC News / Youtube

The Greek Minor Prophets scroll uses the Hebrew word for God, following Exodus 20:7’s warning against using God’s name in vain, and documenting several methods for correctly reading the Hebrew name aloud. The intriguing discovery likely elated the archaelogists involved in the dig, however, as they worked, they stumbled upon something that shocked them.

Finding a Mummified Child

The new Dead Sea Scrolls were an important discovery, however, when the team working on the Cave of Horrors found a partially mummified child, they were far more intrigued. Antiquities authority historian Ronit Lupu told the Jerusalem Post that the child’s skeleton and the cloth wrapping were extraordinarily well preserved.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

He said that due to the cave’s climate, a natural mummification process had occurred, leaving the skin, tendons, and even hair preserved mainly despite the passage of time—precisely 6,000 years. The mummified remains’ age meant that it is older than the Dead Sea Scrolls. Of course, the team had to study the body further to determine gender, age, and cause of death.

Examining the Skeleton

According to a C.T. scan, examiners have determined that the youngster, most likely a female, was between the ages of 6 and 12. She was wrapped in fabric and placed in the fetal position in a small hole. According to Ronit Lupu, it was clear that whoever buried the child had covered her in a blanket and tucked the ends under her, just like a parent would do.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

The youngster also held a tiny bundle of cloth in her hands. Other ancient items found alongside the mummified child were arrowheads and a lice comb. They were not as old as the mummy, though, because the items were from the Bar Kochba revolt period.

The Possibility of Finding More

Apart from ancient text fragments, the latest finds illuminates the Dead Sea Scrolls’ turbulent past. With their value quickly established in 1946, it is not surprising that even now, archaeologists and local Bedouins continue their frantic search for more pieces.

Source: News 360 Tv / Youtube

Since the scrolls were first found, at least one modern museum collection has acquired fake versions of the ancient manuscripts. The significance of the newly discovered document fragments cannot be overstated. That’s why the Cave of Horrors raises the question of how many scrolls and historical secrets are still out there, waiting to be discovered.